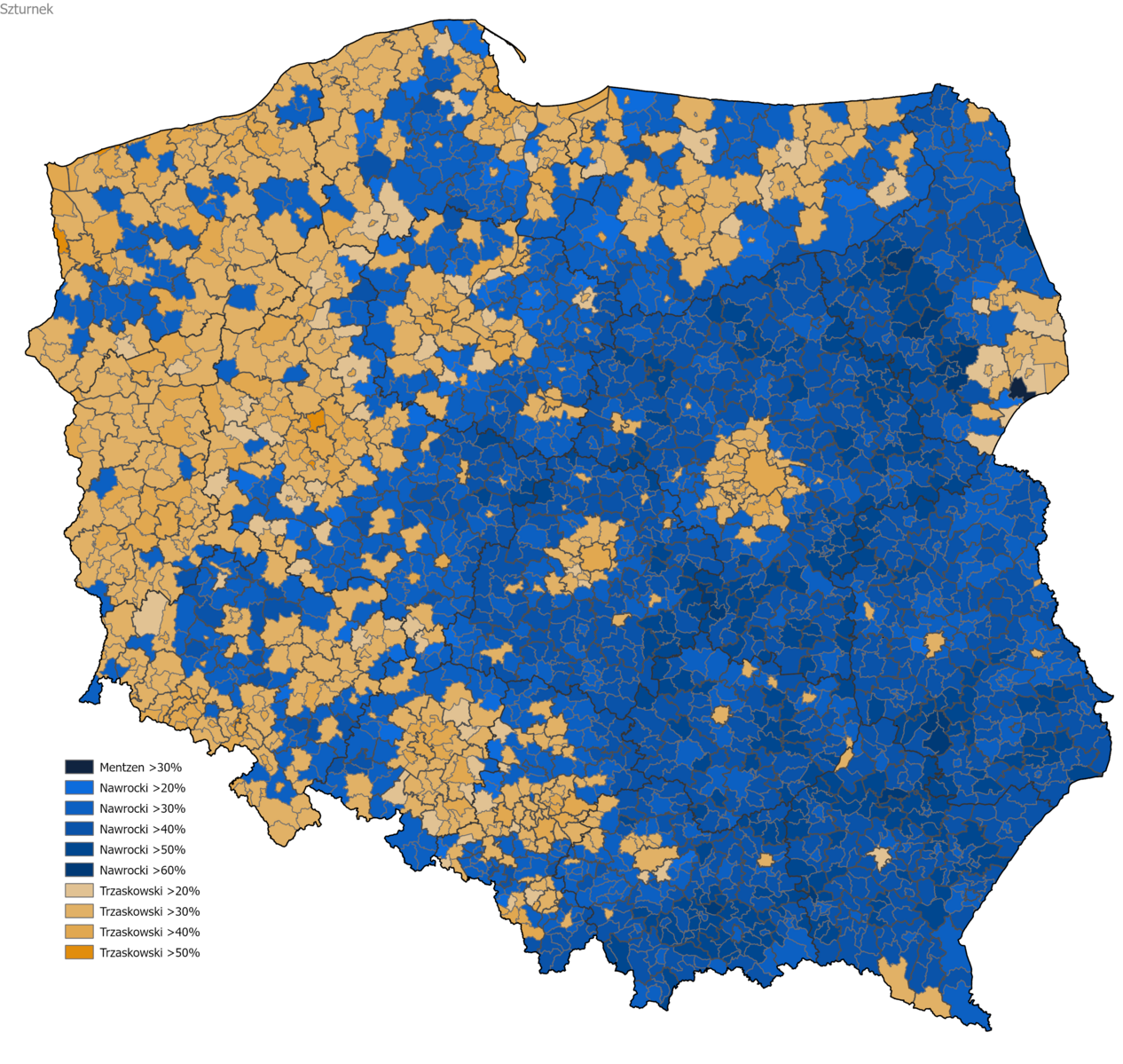

This is very bad news. At a time when Europeans need to step up in the face of American withdrawal and Russian revanchism, the victory of the nationalist candidate in the Polish presidential election will slow down the political affirmation of the Union.

Led by Paris and Berlin, European capitals have every reason to be gloomy. In the Kremlin, on the other hand, champagne is flowing, as the new president, Karol Nawrocki, will do everything in his power to paralyse Prime Minister Donald Tusk, one of the main architects of the European rearmament and the support for Ukraine. A boxer, this historian will have the presidential veto, which he can use to mobilise nationalists and the far right ahead of the 2027 legislative elections. Poland will not stop helping Ukraine, but with such a close result yesterday, the country is now literally split in two and threatened with political paralysis. There will be constant guerrilla warfare between the government and the presidency, but how and why did we get here?

The answer is that in Poland, the left is on the right. This has not always been the case. Between the two wars, the socialists were extremely strong and firmly rooted in the social and internationalist values of the left. After the war, under communism, dissent was essentially left-wing, anti-communist of course, but inspired by social Christianity and the German and Scandinavian social democracies. It was these men, heroes of freedom, Kuron and Mazowiecki, Walesa, Michnik, Geremek and so many others, who won the first free elections in 1989. They thus foreshadowed the fall of the wall, but none of them knew anything about finance, and it was their government that chose to resort to the ‘shock therapy’ proposed by liberal economists.

Price liberalisation, support for the revival of the private sector, the abandonment of ba0nkrupt state-owned industries and the end of food subsidies: these choices have enabled Poland to become the sixth largest economy in the European Union, with virtually no unemployment and sustained growth. The success of shock therapy is hard to dispute, but between factory closures and soaring prices, it initially plunged entire battalions of workers into poverty, the very same people who had brought down communism with the strikes of August 1980 and the birth of Solidarity, the first free trade union in the Soviet bloc.

Their social anger and political resentment were such that their votes brought the communists back to power in 1993. Democracy put the communists back in charge after ousting them four years earlier. It was a spectacular reversal of history, but having become liberal and pro-American, the cadres of the former ruling party continued along the path laid out by the former dissenters. Within a few years, the former communists and the democratic left, yesterday’s adversaries, were wiped off the political map in favour of a duopoly of new forces.

Led by Donald Tusk, the Civic Platform established itself as a major centre-right party after being formed in Gdansk some 25 years ago by a small group of Thatcherite intellectuals. Modernist and pro-European, it is the party of the new Poland, born out of the defeat of communism and at odds with the Church, while the PiS, Lech Kaczynski’s Law and Justice Party, brings together those disappointed by democratisation, opponents of the changing social mores and defenders of the central role of the episcopate.

Founded in the same year as the Platform, the PiS owes its popularity to the lowering of the retirement age and the introduction of very generous family allowances. These costly measures would not have been possible without the budgetary rigour with which the liberals had filled the state coffers, but they have made the conservatives the major party of social protection and the most disadvantaged. They have become the party of the left, a left whose voters have thus moved to the conservative camp.

Particularly apparent in Poland, this phenomenon is common to many former communist countries in Central Europe. In Hungary especially, on one side of the political spectrum are those who have benefited from the transition to a market economy and are not alarmed by feminism and gay visibility, and on the other are those whom the end of communism did not lift out of poverty but plunged into a world in which they no longer find their bearings.

For the voters of PiS, Orban in Hungary or Robert Fico in Slovakia, the left is on the right and the right is on the left because they are primarily seeking a social contract that ensures their economic survival and offers them a moral order that is traditional enough for them to identify with. This explains why, even in Poland, they find Vladimir Putin appealing, while they perceive the European Union as a threat to their national traditions and social stability. This also explains why, in Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and sometimes even Poland, these voters consider it prudent to make concessions by abandoning Ukraine to Russia rather than incurring its wrath without the American umbrella to protect them.

Throughout the post-war period, Poland has been a harbinger of major developments in Europe. This should not be the case again.

(Cover image: Szturnek @ Wikimedia Commons)