Should we or should we not refer to what is happening in Gaza as ‘genocide’ and should we recognise Palestine without further delay? These are the two questions that are now impossible to discuss in Paris without the tone inevitably rising.

So let us try to address them calmly and with all cards on the table.

In Gaza, the Israeli government is guilty of war crimes for bombing hospitals and residential areas, forcing the population to flee en masse and hindering the distribution of food and medicine.

Neither the use of hospital basements to store weapons nor the digging of tunnels under inhabited buildings can relativise these crimes. These are war crimes, but we could only speak of genocide if there had been a deliberate intention on the part of the Israeli authorities to exterminate the entire Palestinian population.

Etymologically speaking, genocide is the murder of a people. In the 20th century, the first victims were the Herero and Nama peoples of South-West Africa, followed by the Armenians, Jews, Roma and Tutsis.

There were many other mass killings in the last century. They were particularly abominable in Ukraine and Cambodia – more than three million dead in one case, more than one and a half million in the other – but it is a misuse of language to refer to these as ‘genocides’ because neither Stalin nor the Khmer Rouge wanted to exterminate these peoples. The former wanted to destroy the independent farmers in Ukraine, as throughout the USSR. The latter wanted to murder all their fellow citizens whom they considered to be opponents, whether real or imagined.

Distinguishing between these killings of millions of people and genocide does not mean denying the horror experienced by Ukraine and Cambodia. Nor is it to diminish the gravity of the war crimes committed in Gaza that we do not speak of genocide there either. It is to stick to the meaning of words and therefore to the reality of things, because, as Camus said, ‘calling things by the wrong name adds to the misfortune of the world’.

This requirement is legitimate and essential, but the problem is that case law does not help, since the courts have been able to classify the massacre in Srebrenica as ‘genocide’ and a war crime seems, so to speak, benign if it is not denounced as genocide.

This is an extremely heated debate and will remain difficult, but the second question is no less so, because ‘How can we recognise, we hear immediately, a state that does not exist?’.

The argument seems unanswerable, but at a time when divided Poland no longer existed, the Ottoman Empire continued to recognise it, and when the Baltic states were nothing more than Soviet republics, the free world rightly considered them to be illegally occupied and annexed states.

Palestine does not exist or (another difficult debate) no longer exists, but there are nevertheless two reasons for recognising it. One is that implicitly it exists, since the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem are, under international law, occupied Palestinian territories, and it is no longer acceptable to ignore this fact.

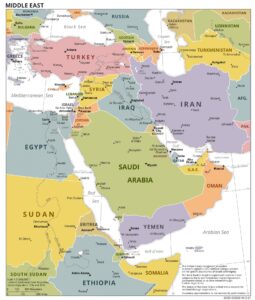

Occupied by Israel, Palestine exists, and since there can be no lasting peace without the coexistence of two states, there is an urgent need to affirm this fully by recognising the one state of the two that does not yet exist.

Once this has been done, the peace talks that will one day resume will be able to focus directly on security issues, the demarcation of Palestine’s borders and the location of its capital, rather than on the recognition of this state, which will already have been achieved. Recognising Palestine does not mean ‘giving Hamas a prize’. It means forcing Palestinians and Israelis to take responsibility by renouncing, on one side, the Mandate Palestine and, on the other, the biblical Israel. Recognising Palestine does not mean taking sides against one another, but breaking out of a deadly status quo and paving the way for the coexistence of two states, the only possible solution to this century-old conflict.

(Cover photo: rajatonvimma /// VJ Group Random Doctors @ Flickr)